I. The Elixir

I suspect Plato would have a lot to say about the Internet. If the philosopher could be zapped forward in time, I’m sure he could find many of the concerns of his time amplified in this information age. No doubt, he would feel compelled to orate many discourses (or write a Substack or two) about the disconnect between digital shadows and reality, that our attention spans are growing ever shorter, that our memories are atrophied and what passes as intelligence is often just sophistry.

I’ve no doubt the cascade of information that fills modern life would be a target-rich environment for Plato’s thoughts about knowledge and remembering. In his imagined dialogue between Socrates and Phaedrus, the characters pose questions about what it is to really know something and how memories compound into wisdom.

A serious problem began with the invention of writing, Socrates proposes. He is convinced that to write things down is to outsource memories; a thing completely inferior to retaining knowledge because you truly know it. Like shadows flickering in his famous cave, Plato sees written words as mere images of something real – a memory stored in the soul.

In Plato’s dialogue, Socrates recounts the mythical story of Theuth, the Egyptian god who came up with the idea of writing. He went excitedly to present his “elixir of memory and wisdom” to the god-king Thamus, who sagely points out that inventors are not the best judges of whether their inventions are harmful or useful. In fact, he tells Theuth that his fascination with his own invention has prevented him from seeing that writing will do the exact opposite of what he intends:

“For this invention will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory. Their trust in writing, produced by external characters which are no part of themselves, will discourage the use of their own memory within them. You have invented an elixir not of memory, but of reminding; and you offer your pupils the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom, for they will read many things without instruction and will therefore seem to know many things, when they are for the most part ignorant and hard to get along with, since they are not wise, but only appear wise."

Plato’s dialogue, Phaedrus.

II. Nothing But a Memory

You are what you remember: In the 17th century, John Locke proposed a theory of identity which has faced much scrutiny since. He submitted that human identity is contingent on an intelligent creature’s ability to “consider itself as itself, the same thinking thing, in different times and places.” Remembering is indispensable to that process, so “memory is a necessary and sufficient condition of self.” If one can’t remember an experience, he argued, then it cannot form who you are.

You are what you experience: In the 18th century, David Hume pitched another theory of identity. He argued that there is no such thing as a self, rather, humans are a bundle of perceptions, imprinted on them by their environment. So, “Hume…claims that you can’t be the same person from one moment to the next, the idea of your ‘self’ doesn’t persist over time and that there is no same you from birth to death.” Memories are, then, not a foundation for identity, but a tool for relating your past perceptions to your present “self”.

You are what you believe: The 20th century, with its fresh focus on individualism has taken a different tack – Daniel Winnicott’s idea that we have a true self (and that it is moral and good) is proving hard to shake:

The true self is different from the self, which is made up of a blurry combination of your physical appearance, your intelligence, your memories, and your habits, all which change through time. The true self is what people believe is their essence. It’s the core of what makes you you; if it was taken away, you would no longer be you anymore.

By this calculation, someone who suffered severe memory loss from Alzheimers is “more himself” than another who lost his “moral faculty” from frontotemporal dementia. But pitting memory against goodness is a strange game. In an episode of a Brief History of Power podcast Dr Koontz reminded listeners that:

“The muses are the source of all, all beautiful arts and knowledge and endeavors in Greek mythology. And the source of the muses is their mother memory. Without memory, you don't have anything else.

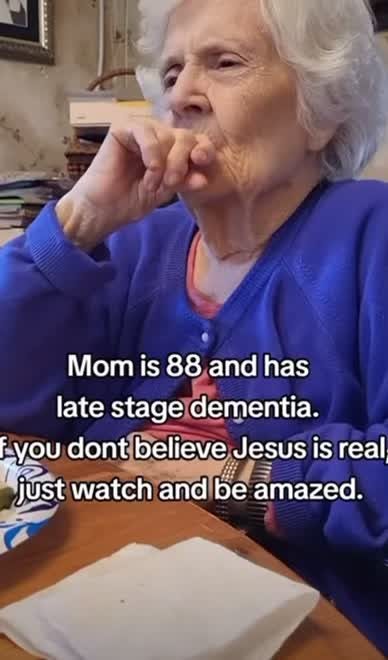

If we are no more than memories or experiences or self-identification, what becomes of our faith if we forget who Jesus is? “Modern culture and much of modern Christianity lead us to think that our personhood is constituted by our ability to reason, to act, and to produce. But from the wilderness, we learn that beyond anything we can think, do, or produce, we are known and loved by God. We are held in God’s memory even when our own fails us.” (source)

III. Digital Soul

“What you don’t lock up inside your heart, the world will consume.” (Charlie Peacock “Slippery Pearls”)

Today, swamped by a deluge of data, we file things away in all sorts of external places; not just journals and notebooks, but on phones and hard drives. It is part habit, part coping mechanism. Mental energy is spent, not working to remember, but just deciding what you need now and what you might need later. Then if you can’t decide, you can always leave it on someone else’s computer in a cloud.

The abundance of storage space and tools to find things again enable a form of digital hoarding. But we hoard in a variety of ways. One professor even sees a generational divide between the digital natives he teaches and people his own age for whom the internet emerged later in their lives. “While older folks still imagine stored information as a "nested" system of files and directories, younger people are visualizing data more like a ‘laundry basket’— you search for what you want when you need it.”

Digital memory is the failsafe. Studies have concluded that people tend to hold onto important things. If “they believe that [remembering] is the only way they will have access to that information in the future”, then they will commit it to memory. But researchers found the converse to also be true. People “who expect to be able to search for answers to difficult questions online are less likely to commit the information to memory.”

In the end, they contend, it is no more an admission of defeat to google something than it is to look it up in a book or ask a friend. Columbia University psychologist Betsy Sparrow suggests that memorizing is “overrated” anyway and time could better be spent critically thinking and understanding concepts.

IV. Machines Can do the Work

A study from the University of Texas found that the ease of searching for something online feels much like retrieving details from your own memory. In fact, participants in the research quickly forgot that they had searched online, mistaking discovered answers for their own memories. They overestimated how much they knew as “the boundaries between internal and external knowledge begin to blur and fade…The research offers a cautionary tale. It suggests that in a world in which searching online is often faster than using our memory, we may ironically know less but think we know more.”

This raises the question: “What does it matter whether we got the information from an external source or from our own memories? It is still something we ‘know’.” After all, humans have been finding answers in books for centuries. The concerns of the study’s authors were twofold. Firstly, they warn that the seamlessness of internet searches gives less time for assessing the information; googling was rather like mainlining data straight into your memory. Secondly, “when we immediately jump to Google, we don’t do the remembering…We’re not exercising those muscles.”

Does outsourced remembering degrade our actual memory capabilities? The jury is still out, but tech journalist Shubham Agarwal wrote about his experience using an A.I.-memory assistant for three weeks. The bot “promised to help me recall what I've been reading” and it did, he says. Yet Agarwal is pretty sure his own memory has worsened.

The bot’s developer says the vision for this product is to give humans “perfect memory” by placing the collective knowledge of humanity into a big A.I.-monitored bucket, available to anyone to dip into (well, their subscribers at least). Echoing the work of Prof. Sparrow, a company spokesman insists that leaving inane information in the keeping of machines frees humans up to do what they do best – thinking, creativity and analysis. A kind of mental labor-saving device, as it were, like an automobile or washing machine. In fact, fans of digital memory bots say the machines will do it better anyway. "With assistance from AI, humans may be able to enjoy more of life, embrace forgetfulness, and learn to weave AI into our every day."

Perhaps the issue is not so much that we allow machines to remember for us; humans have stored a lot of their memories in libraries since antiquity. But every new technology comes with trade-offs, as was the case with the plow, the printing press, the musket or the production line. It is assumed that humanity embraces the benefits, absorbs the harms and life goes on. But the internet, screens and now A.I. are changing us in ways we won’t discover for generations to come.

It is worth considering carefully which aspects of life we hand off to machines. Maybe we can dispense with learning handwriting, remembering recipes or how to read maps. But what is lost when we give over decision making to an algorithm? What is lost when we promote counselling chat bots for the melancholy? What is lost when our youth congregate more online than in real life? What is lost if we let robots tend to our elderly? What moments did we miss while we were trying to capture it on our phone?

Writer and journalist Christine Rosen says we are losing more than we think when we lose sight of the fact that there are some things only humans can do. Can we remember how to be bored, how to daydream, how to read emotions in the face of another? We need to “reintroduce friction”, she says, choosing awkward and slower human interactions over machine-enabled convenience whenever we can.

Machines can do the work, so humans have time to think..

V. On the Frontier

The burden of knowledge argument posits that the sheer volume of information in the world today means that the amount you must understand before you can even begin to innovate or progress, is now unattainable; the distance to the “frontier” of any field extends further with each passing decade and will take more than a lifetime of learning can absorb. In reality, it’s never been possible to know everything, but there once was such a thing as a “Renaissance man” – one who is a pioneer in many fields – which seems quite unfathomable now.

Using lessons learned in one sphere to solve problems in another is a skill less valued today, and such a skill is rarely taught. In her essay warning about the dangers of overvaluing “expertise”, Dorothy Sayers observed that “the intellectual skills bestowed upon us by our education are not readily transferable to subjects other than those in which we acquired them: ‘he remembers what he has learnt, but forgets altogether how he learned it.’”

The ability to follow a trail of knowledge to its particular pinnacle means you can be the world expert in your field, but it can be lonely at the top. The myopic focus on a single subject can also mean you know very little about anything else. Surgeon Atul Gawande has pointed out that access to vast amounts of information has turned every doctor into a specialist, meaning patients see more doctors for each of their ailments but still get incomplete care.

Hopefully, the Renaissance Man is not a relic of history, for he is much needed today. It’s not necessary to know everything about something to understand it, as writer Walker Larson argues. Quoting Mortimer Adler makes the issue clear: “There is a sense in which we moderns are inundated with facts to the detriment of understanding.”

VI. The Internet Is Not Forever

If one mind can’t know or recall every important thing, then outsourcing that information seems necessary. But the assumption that the internet is a bottomless pensieve containing things we need to remember yet can’t fit in our heads has a fatal flaw – the internet is not forever. “Digital decay” is a term for the way internet links break, websites disappear and social media posts are no longer accessible. Researchers found that 40% of webpages created in 2013 no longer exist. Hardware failures and software incompatibility, teamed with data corruption means that a degree of obsolescence is baked in to the digital cake.

VII. The Gatekeepers

Let’s go down memory lane, shall we? Do you remember the time that Donald Trump, the man who Republicans nominated to run for president was almost assassinated at a campaign rally? If that event had slipped your memory, you’re not alone. It seems the internet forgot too. A few reporters asked various chatbots to tell them about the near miss that almost took Trump’s life and were given the digital equivalent of blank stares. "There is no evidence or credible reports indicating that Donald Trump was almost assassinated in Butler, PA, or at any recent event," said ChatGPT.

Meta blamed “hallucinations” – where a learning machine makes stuff up – for its bot’s poor memory. Well, sure, Language Models are still a bit wet around the ears, so we could cut them a little slack. But Google was also guilty of trying to forget this particular event. Its autocomplete feature (where the search suggests words that it thinks you might be looking for) refused to offer Trump’s name when a user entered a search about the assassination attempt, instead going with Truman in reference to a little known event in 1950. Google said it wasn’t on purpose, but that the algorithm was built with protections to preclude things to do with “political violence.”

In this age of coordinated panic over misinformation, some are busy stealth editing to make you feel you are alone or crazy for believing the truth. Journalist and blogger Eli Lake published a compelling podcast about the corporate media’s most recent attempt to wipe the public memory – the circumstances around the President’s exit from his re-election bid:

“Overnight, the press went from picking Joe Biden apart as an out-of-touch, senile, selfish old man to praising a great patriot who understood when it was time to exit, as if the same media wasn't pushing him off the stage….And that his successor, who was widely understood as a drag on the ticket just a few weeks ago, is now the second coming of Barack Obama.”

Lake draws comparisons between our age and Soviet Russia’s attempt to control information: “One of the striking features of late Soviet Russia was that nobody believed anything the party said.” It’s true that sending things down an Orwell-style memory hole is not quite possible in the age of screen shots and such, but that will not stop the gaslighting. As Lake says, “[Today’s] memory holes do not destroy the evidence of the past, but they can bury the evidence under a mountain of nonsense.”

He remembers a Soviet joke: “The future is always certain. It's the past that's always changing.”

VIII. The Past is a Foreign Country

You would imagine that words inked on a page are fairly tamper-proof. Yet, if you have old dictionaries, old editions of the Bible, old Roald Dahl books, you will notice that things change with each print run. Some of it is just changing language, fresh translations or similar, but some of it is designed to overlay the author’s work with updated sensibilities. Progressives will cry “book ban” when governors or parent groups remove pornographic groomer content from school libraries, but woke editors are obliterating texts by changing them in the name of inclusivity.

The disdain for those who came before on the part of modern men is a recurring theme on the Brief History of Power podcast. Revised and sanitized to suit the mores of our confused age, history becomes more about us than about the people who made it, who survived so we could be here. But letting voices from the past speak is incredibly valuable:

“The good of [learning] history is that it makes you much less of a child, also spiritually, than you otherwise would be…You get the vicarious experience of previous generations and thereby become wiser in your own right for your own day…History is a display of God’s providence, it’s what you learn when you're learning about history..So a Christian is not only instructed and delighted by history, he is also moved to awe and praise by history because what he sees is his God working out what redounds to his people's good through those events.” (source)

IX. Pagination

“When you read a book, things like page numbers and the physical ability to hold and turn pages help your brain make a mental map of the information the book presents you with. Websites, however, don't have those kinds of memory triggers. Because of this, multiple studies found that participants who read offline performed better in comprehension, concentration, and recall than participants who read online.“ (source)

Given that humans are corporeal creatures in a physical world, it makes sense that the digital is a tool of dislocation, as I wrote some time ago. It has a frictionless quality to it – bland and easy. Untethered to any locality, it tends to render the body and physical things unimportant. Endless scrolling leads to a feeling of displacement while “context collapse” (where the lack of delineation between types of information and different audiences) leaves us “unsure how to act or be.” Making connections between nebulous pieces of information is uniquely difficult; turning that isolated data into memories is harder.

By contrast, physical media is necessarily connected to embodiment. Turning over a vinyl record, flipping the pages of a book or even feeding film into a camera gives a sense of beginning and end:

“Living in a digital age, where options and capabilities so often seemingly approach infinity, the analog connects to our unique human condition of being embodied souls: capable of participating in the infinite while necessarily being rooted in the particular.” (source)

Much to the chagrin of transhumanists and their desire to join the great Singularity, the digital is contingent on the physical. "Wave that magic wand and everyone holds Bitcoin, goes to school via Zoom and Youtube, and can work anywhere with a wifi connection — what do we, as a nation, build? The very things we want flexibility to enjoy are only possible because someone made a commitment to a community and a place." (source)

X. Remember Me

In the beginning was the Word..

Plato seems dismayed at his own conclusion; that the written word is only a dim reflection of a greater reality seems to disappoint. Such a confession leaves him wishing for a better kind of word, a truer reality:

SOCRATES: Is there not another kind of word or speech far better than this, and having far greater power—a son of the same family, but lawfully begotten?

PHAEDRUS: Whom do you mean, and what is his origin?

SOCRATES: I mean an intelligent word graven in the soul of the learner, which can defend itself, and knows when to speak and when to be silent.

PHAEDRUS: You mean the living word of knowledge which has a soul, and of which the written word is properly no more than an image?

I guess he could not have imagined Jesus, the true Word of God – the letter and the spirit, the image and also the true reality. He, the Logos, eternal and unchanging.

Your word have I hidden in my heart.

Plato might object to the idea of writing things down; to him, a weakened version of true wisdom. Yet our Creator is clearly not averse to writing things down – the Word of God has been written down for us! Those who read it are blessed. Those who understand it gain wisdom. Those who trust it will not be shaken.

Lord, remember me when you come into your kingdom.

This Ancient of Days does not struggle to remember his promises. Forgetting our sins is a deliberate act. More than that, in him all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge are hidden. He does not change like shifting shadows.

Do this in remembrance of me.

By participating in his memorial feast, we are made immortal. Baptised into his death, whatever has been lost will be outweighed by the glory of the resurrected life in his eternal kingdom.